School and Studying

Schoolwork is a major factor in the amount of sleep students get, especially when large tests and finals are looming on the horizon.

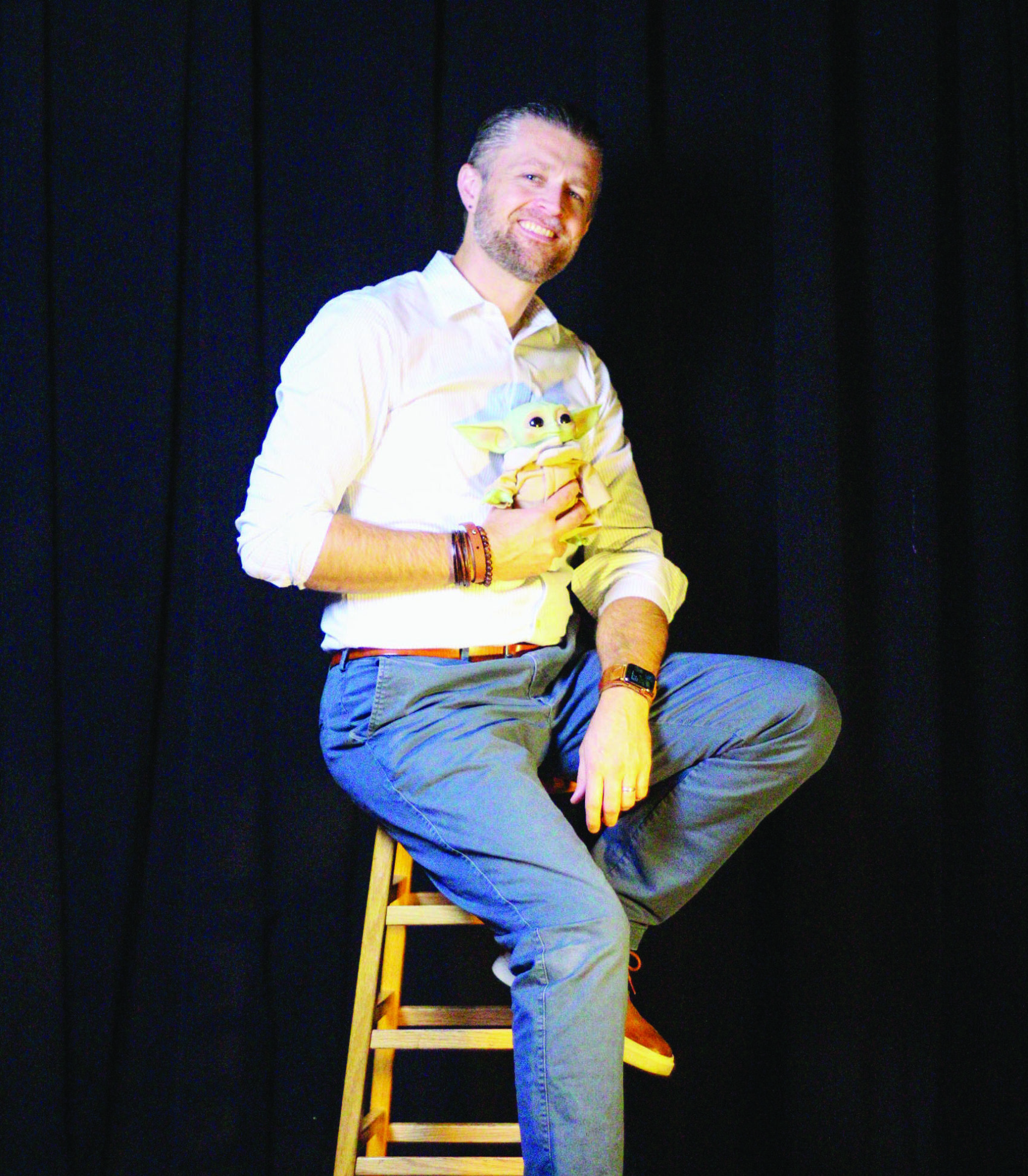

Senior Hayden Boersma knows this all too well. He often finds himself staying up to catch up on schoolwork. Recently, he pulled an all-nighter to prepare for his AP English and AP Microeconomics finals.

“I stayed up for like 38 hours, and I told myself I need to fix my sleep schedule now. So, I wanted to go to bed early the next night but I ended up staying up until 1 a.m. without even realizing it since I’m so used to it,” Boersma said.

Margolis also repeatedly sacrifices his sleep for extra time to finish work. Like Boersma, Margolis stayed up all night during finals week to finish his project for AP Calculus BC and study for his AP Computer Science Principles final.

“I don’t think I procrastinate that much,” Margolis said. “But I often find myself looking at the clock, thinking it’s not too late and seeing it’s 1:30 a.m., and I have two more assignments left. That’s basically every night.”

Even though students like Margolis and Boersma stay up to do work and increase their chances of getting better grades on tests, Country Day Social-Emotional Counselor and Educator Pat Reynolds said it’s counterproductive.

“People who stay up all night and study and then don’t get any sleep are not going to be able to access what they’ve been trying to learn because it hasn’t gone from short term to longer term memory,” she said.

Not getting adequate sleep can negatively affect students’ performances on tests; sleep deprivation limits how fast you can finish a task and how quickly you can think and recall information you may need to answer a question, he said.

Dr. Dhawan expressed similar views.

“The night before a test, you should try and get as much rest as possible,” Dhawan said.

Boersma and Margolis are well aware of the lower energy levels associated with sleep deprivation.

“That’s my secret, Cap. I’m always tired,” Margolis said, parodying a famous scene in “The Avengers.”

Boersma also has seen problems arising from sleep deprivation seeping into areas of his life other than academics.

With hopes to go pro in the video game Valorant, Boersma has to set aside a few hours every day to consistently practice. However, he notices that his reaction times are often slower and that he can’t play as well when he hasn’t had enough sleep. This makes doing well in important tournaments difficult, Boersma said.

Despite various attempts to correct their sleep schedules, both Boersma and Margolis have failed repeatedly.

For Margolis, sleeping early isn’t an option. For one, he can’t do his work until he’s in a quiet environment — something that only happens in his house late at night. Secondly, if he went to sleep early, he wouldn’t have enough time to stay on track with his work.

“I’m sort of in this cycle. Like I have so much work. I have so much work. I have so much work, and then suddenly it’s the weekend,” Margolis said. “Then I sleep in during the weekend and end up staying up late to do everything I want to do in a day. So, I end up just repeating the cycle over and over again.”

Although he finds days where he can get everything done and get adequate sleep, they’re rare.

“It’s an endless cycle of your health bar depleting until you can grab that little power-up of sleeping for 10 hours on that one lucky night,” Margolis said.

Boersma can’t break out of his cycle because he doesn’t fall asleep until around 2 a.m., despite trying to go to bed at midnight.

“It’s tough,” Boersma said. “Going to sleep is something everyone does every single night, but no one actually knows how to go to sleep. The more you try to force sleep, the longer it takes to fall asleep.”

It is not uncommon for teenagers to have what is called delayed sleep phase disorder, Dhawan said.

“Adolescents can have delayed sleep phase disorder where they can’t go to bed until late and wake up until late. Teenagers that have DSPD will probably do poorly in class during the first few periods because they are just sleep deprived and can’t function normally at 8 a.m.,” Dhawan said.

Unfortunately, it takes a long time to push back your bedtime to fix a delayed sleep phase, Dhawan said.

“There’s no quick fix. You’re not just going to decide overnight that you’ll be able to sleep an hour or two earlier,” he said.

Junior Malek Owaidat’s sleep schedule is shifted later — and fragmented. On weekends, he goes to bed around 5 a.m., waking up around 1 p.m. or 2 p.m.. But on weekdays, Owaidat cannot sleep in. Instead, he takes naps in the afternoon after school ends and a nap in the evening after his soccer practices. In total, he said he gets nine to 10 hours spaced throughout the day.

Fragmented sleep phases often result in unrestfulness because the body is usually not getting the REM sleep it needs, Dhawan said.

During evening soccer practices, Owaidat feels more fatigued. But, he said it does not hinder his ability to focus or pay attention in class.

Procrastination is the primary cause for his late bedtime. Owaidat has his phone and his PC in his bedroom. While the PC is not a distraction, he said the phone can be.

Owaidat said his sleep schedule has become worse recently. Earlier in high school, he went to bed by 2 a.m. or 3 a.m.

Since he has kept the same sleep schedule for so long, he has found it hard to break.

The inconsistency and “awkwardness” of the hybrid schedule also makes developing a consistent sleep schedule difficult for Boersma.

“Nobody knows what’s going on except the students sitting there because they’re the ones who are suffering through it,” Boersma said.

Margolis also said that the additional work that six classes back-to-back brings makes it hard for him to find free time while getting enough sleep.

“For AP Calculus BC, we have all these extra assignments,” he said. “And I’d love to do them, but I can’t do them because I either don’t have the time or when I do, it’s the one time I can take a break. Am I going to choose that one break or more homework?”