Last month, Joan Meyer, owner of the Marion County Record newspaper, collapsed and died one day after law enforcement raided her office. The raid responded to allegations that the paper’s journalists violated a local restaurant owner’s privacy by discovering information about her driving record.

Reporters received a screenshot of her DUI conviction but refrained from printing it until verified by public record searches.

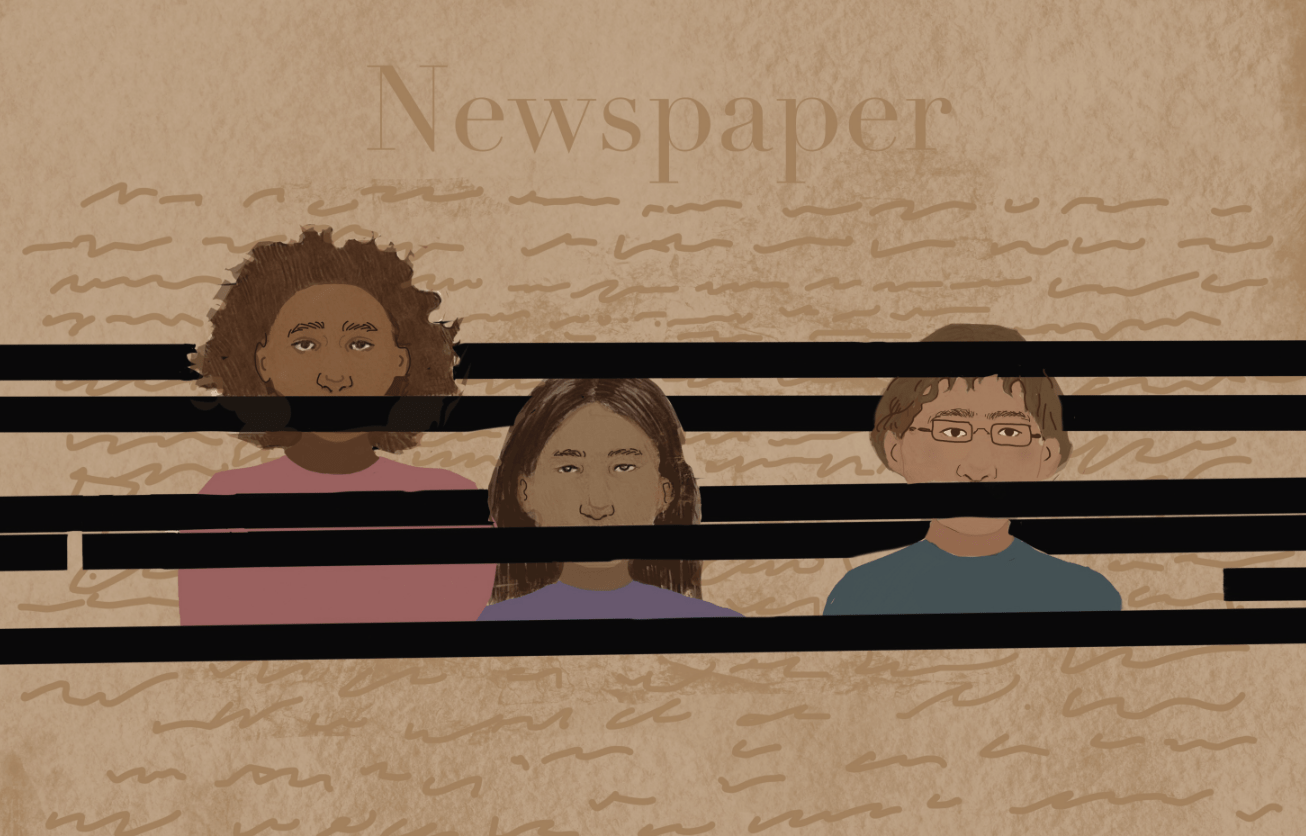

Violence and backlash against journalists is not uncommon; in fact, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) documented 400 journalist killings from 2016 to 2020.

Although this trend has been declining, with 55 journalists killed in 2021, other forms of violence against journalists persist, such as journalist imprisonment, online violence and harassment, physical attacks and a lack of impunity for these crimes.

Silencing journalists through violence is censorship, plain and simple. It does nothing but undermine the purpose of the industry.

According to the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), there are four components to the journalistic code of ethics:

- “Seek truth and report it.”

- “Minimize harm.”

- “Act independently.”

- “Be accountable and transparent.”

First, journalists shoulder the responsibility of gathering, recording and reporting accurate, unbiased information in a timely manner to inform the public.

These reports are then published and made accessible to the public, and become the most-accessible public record available. We are the scribes of history.

However, ethical journalism can only exist with cooperation from both our subjects and our sources. Ethical journalism requires ethical journalists as well. As journalists, while we vow to balance an individual’s privacy with the public’s right to knowledge, we also expect those who provide information or interviews for our stories to uphold certain agreements.

Specifically, we request that sources do not ask for content to be removed, edited or taken down from news publications.

In alignment with most publications, The Octagon has historically followed a strict policy of transparency, in which reporters are tasked with informing interviewees about what being published in a newspaper truly entails. This policy can be found in The Octagon Handbook.

Additionally, interviews are only conducted after an interviewee has given full consent with the knowledge of the irreversible consequences of being published and on the record.

Many don’t realize posing for a photograph and sitting for an interview is considered giving permission to be published.

Takedown requests impede our goal to report the facts — they are a form of censorship and violate the journalism code of ethics and a publication’s right to independence.

Therefore, we ordinarily cannot carry out takedown requests.

Even if a piece that is attributed to a person contains an unflattering photo or a quote that they no longer agree with, publications are not entitled to take it down, for the interviewee was informed of the consequences already. A change of mind, heart or identity is not necessarily justification for a retraction.

The Octagon’s reporters tape interviews and work with editors to omit editorializing the news and ensure fairness.

Before accepting interview requests, the general public should think about whether it is comfortable with sharing this information with the public.

There are exceptions in which it is appropriate to alter a story that has been published or posted online.

The first situation is when a story has a factual error or when new information has surfaced. In these instances, the publication would post a correction or updated version, indicating that edits have been made to the original story.

The original story would not be deleted, however.

Another instance that warrants a correction is when libel is present in a piece.

According to the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), libel is defined as a false statement or information published about an individual or entity that is damaging to their reputation.

Libelous or untrue statements, especially those made in print, can have serious consequences for those they are written about.

While journalists work to report accurate information, these mistakes have been made. The statute of limitations, or the timeframe within which legal actions can be taken against a newspaper in libel or slander, is generally one year from the publication date as decreed in the 2021 California Right of Publicity of Law.

In these situations, it is our responsibility to take accountability and to rectify the problematic parts of the story. We correct the inaccurate information in an attempt to minimize harm to those involved.

It is crucial to note that even if a publication removes content, there is no guarantee that the content is completely erased.

With the spread of information being invigorated by social media, there is a possibility that the deleted or original version exists elsewhere.

Once a story is published online, it remains there forever. The permanence of the Internet renders takedown requests practically useless, even if the situation warrants one.

Besides, physical print copies of the paper that contain the original version the story will always be floating around.

Although publications are responsible for fulfilling their duty of minimizing harm, it is unrealistic to expect that all traces of a faulty print will be deleted from history.

Published works are permanent.

Journalists report the facts — we do not make it. Stories can change over time as details and evidence become available, and we respond by posting clarifications and corrections.