There are over 25,000 public and private high schools in the United States — each year, there are at least 25,000 valedictorians, student body presidents and club leaders vying for admission to top colleges.

Yet there are around 2000 freshman spots at a place like Stanford, meaning thousands of qualified applicants — valedictorians, student body presidents, club leaders — are rejected.

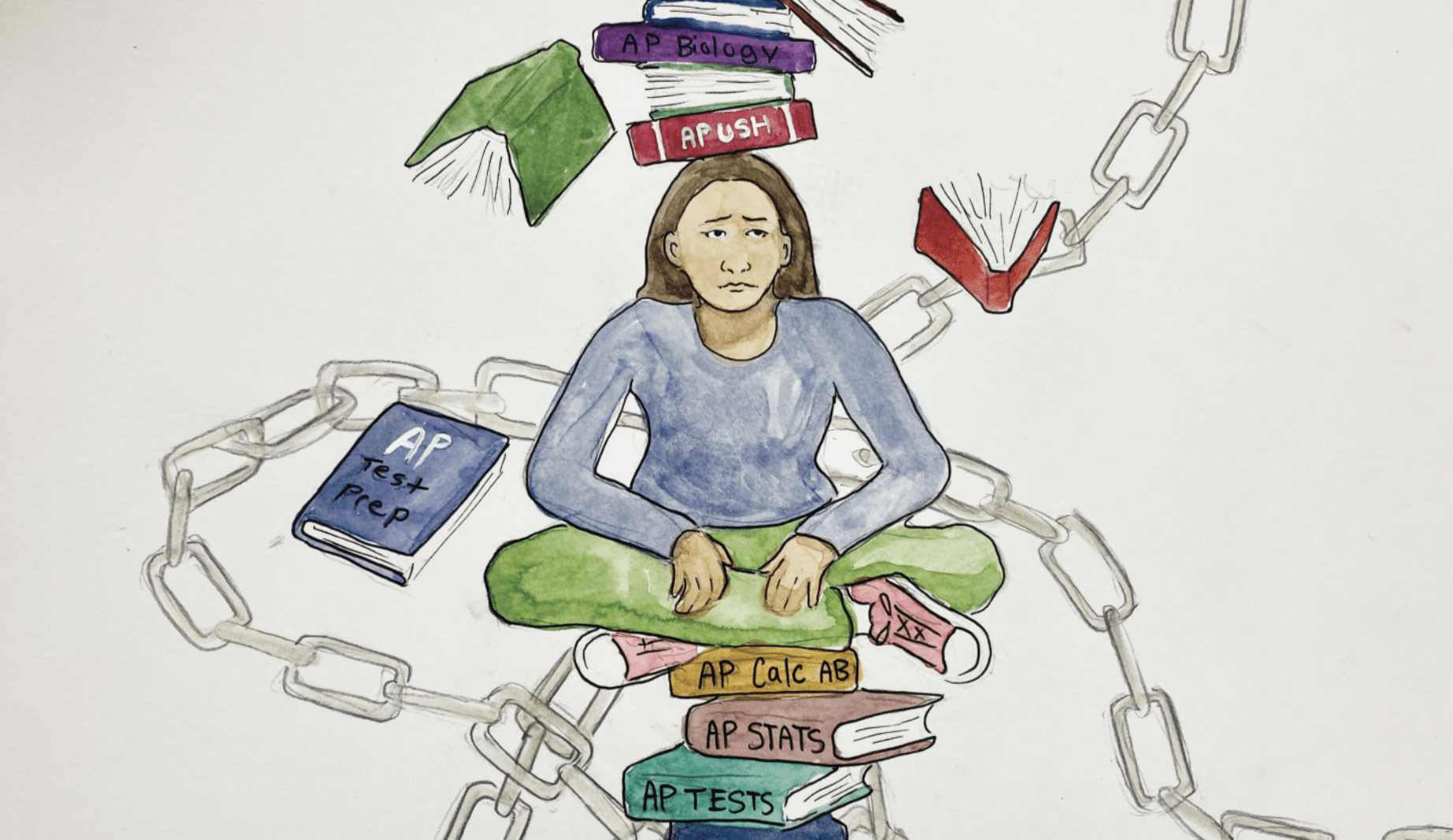

In this obsessive quest for admission to an “elite” school, students take on obscene amounts of stress:

“Why [insert ‘elite’ university here] REJECTED me, the ‘perfect’ student,” laments a heartbroken student on YouTube.

“How to get into X: The Complete Guide,” offers false hopes and platitudes.

“Do I have enough APs to get into X?” applicants agonize.

These anecdotes show the immense pressure students feel to get into top colleges.

But the hard-to-swallow reality is, where you go to college doesn’t really matter.

In the words of one admissions officer:

“Just as a Gucci belt or a Chanel purse won’t automatically make you stylish, the brand on your degree can do only so much work for you.”

Highly successful people like Stephen Spielberg (Cal State Long Beach), Warren Buffett (University of Nebraska), Sergey Brin (University of Maryland), and Kamala Harris (Howard University) are living proof.

The 2023 Fortune 500 list showed that only 11.8% of Fortune 100 CEOs obtained their undergraduate degrees from Ivy League institutions.

You are not defined by where you go to college.

Every college is full of smart, curious and excellent professors who want to help you achieve your goals.

Almost every college is going to have some major you love, a dynamic campus life and opportunities to make amazing lifelong friends.

Many companies love to hire scrappy kids who don’t attend “elite” institutions, who have to work hard to get in the interview room — different paths, similar destinations.

A recent trend is that the number of college applications to institutions have been growing, but mostly towards big name schools. The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) set records in application numbers last year.

This benefits prestigious colleges: their class size remains the same, but they lower their acceptance rates and outwardly appear more prestigious.

Simultaneously, because of relaxing restrictions — like test scores becoming optional — the metrics colleges use can be more subjective and random than ever.

Therefore students need to apply to more places to be sure that they get in somewhere, increasing the number of applications.

This creates a positive feedback loop among top colleges, and with lower acceptance rates funneling even more attention and applicants. The trend of more applications to top schools reinforces their perceived prestige and exclusivity.

Most high school students can barely name any non-top 50 colleges that aren’t in their area until senior year and the college application cycle.

There needs to be more attention on a wider variety of schools.

Country Day’s old tradition of M&M man helped bring attention to other schools. For Country Day, this was something that was the old practice of the M&M Man helped with. Each morning meeting, mini morsels were offered to seniors who announced each of their college acceptances — usually to cheers and affirming applause.

This practice succeeded in bringing awareness to the rest of the high school of the kinds of colleges that students do attend or apply to that aren’t elite institutions or traditionally well-known.

Positive experiences like this can broaden students’ perspectives on college options.

It turns out, the majority of colleges admit most students who apply — 75% of schools that use the Common App admit more than half of their applicants.

Plenty of spots are out there, just not at a small set of schools.

But this obsession, this unfounded hype has still taken up a staggering amount of our brainspace.

It’s not uncommon for students at Country Day to take 10, 12 or even 15 Advanced Placement (AP) courses across four years — undoubtedly a commendable undertaking. Some schools even require students to take AP exams.

The College Board and test prep industry profit enormously from this frenzy, but more APs don’t necessarily help students.

The College Board rakes in over $1 billion annually from exam fees. The test prep industry is worth billions more. Some families spend thousands on test prep.

The counter-argument would be the recent move to make tests at many top schools. This supposedly takes the pressure off students.

However, this change actually increases pressure in other ways. With tests optional, students feel the need to take more AP courses and do more test prep and coaching to get SATs and ACTs in an even higher percentile bracket so the scores really stand out and matter.

Parents sometimes also push PSAT prep, hoping for a National Merit Scholarship level score or other designation students can highlight on applications, even for colleges that don’t allow test scores (like the UCs).

Taking APs is a great way to demonstrate rigor and investigate a subject you’re interested in. But piling them on, “AP-stacking” per say, yields diminishing returns and needless anxiety.

Rigorous class loads are still good — passing your college calculus and science requirements, for example, can be extremely advantageous over time and saving students a year later on.

Life is too short to waste time doing some class or activity to further your college admissions rat race ranking.

Emphasis on extracurriculars has even, to some degree, spawned an exhausting culture of résumé padding that complicates the process more. Padding resumes with activities you’re not truly interested in also adds unnecessary stress.

How can we justify allowing ourselves, our students or our children to stake their self-worth and precious adolescent years to the capricious whims of a system that, by all measures, ranges from being systematically unfair at best to a complete gamble at worst?

In this manic environment, students fear deviating from expectations or pursuing their true passions, lest it jeopardize their chances at top schools.

Meanwhile, rates of stress, depression and suicide continue rising; over 30% of kids ages 13 to 18 have issues with anxiety. Studies have proven depression among teenagers increases over the school year, dropping over summer break.

Education should instill a lifelong love of learning, not serve as a checklist (stress-list) to get into college.

It’s supposed to expose you to all sorts of ideas, people and things that you can do and want to do with your life — that you find compelling.

It should spark curiosity, empower independent thinking and prepare students to navigate and have an impact on an increasingly complex world.

But easier said than done. This obsession is deeply ingrained in our culture. We equate elite colleges with success. Adults feed the frenzy too — pushing kids to pad resumes, worrying over rankings.

The solution: rather than fixating on external validation, students should feel free to follow their intellectual and creative instincts — and society should stop equating college pedigree and signaling with human value.