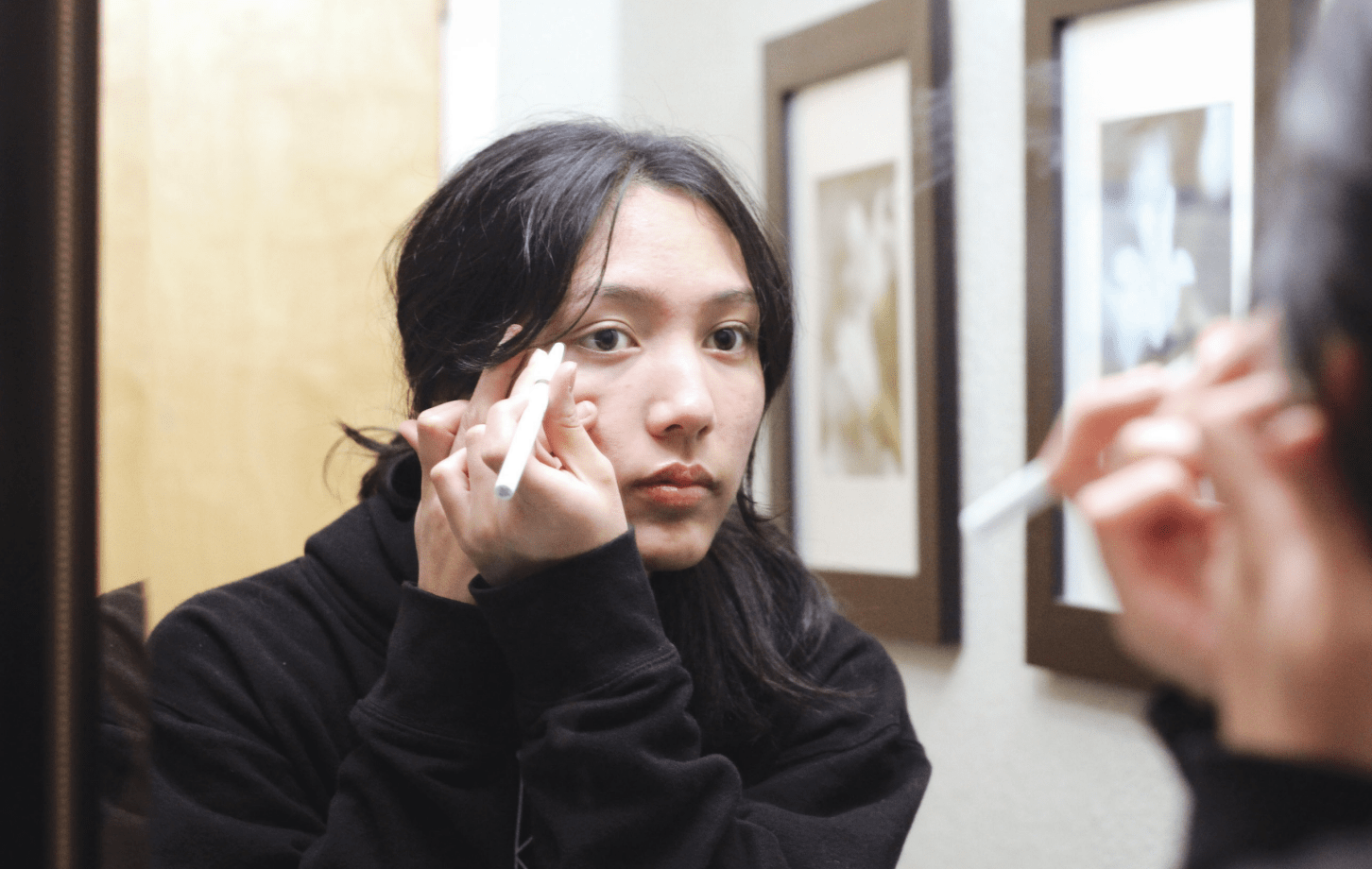

When senior Grace Zhao was in seventh grade, she discovered Korean beauty and makeup products. Enamored by the stunning visuals of celebrities flooding her online feeds, Zhao was sold on the concept that she needed a potent Vitamin C serum to correct her dark spots.

Like many other preteens and teenagers, Zhao was influenced by social media to buy into anti-aging beauty trends intended for adult consumers.

She said that as a constituent of the Internet’s younger audience, she found products and trends marketed toward older teenage and adult women alluring by nature.

“I got a lot of content that made me shop and act like an older girl, even though I wasn’t,” Zhao said.

Zhao realizes in retrospect that the bedrock of her perception of beauty in middle school was formed by the content she consumed online.

“Looking back now, it’s just absurd to me because I didn’t need that at all, and that wasn’t something that was appropriate for my age,” Zhao said.

This pattern of middle school girls consuming anti-aging and beauty products has only grown stronger since Zhao was in seventh grade.

In 2023, the term “Sephora kids” became prominent online. It refers to the increasingly younger demographic of shoppers at cosmetic stores.

Adult shoppers and Sephora employees have shared horror stories on the Internet about the influx of unaccompanied 10-year-olds running rampant in beauty stores: throwing tantrums, destroying displays and disrespecting those around them.

“I’m not sure why the new trend for 10-year-olds is skin care and $80 makeup,” said TikTok creator @_giannalove in a video. “If that was the trend when I was growing up, my mom would have literally laughed in my face.”

In addition to purchasing products, some “Sephora kids” create content showcasing their consumption habits, encouraging their peers to do the same.

For example, on YouTube Shorts, Zhao frequently sees videos of preteens’ makeup and clothing hauls, mimicking older influencers; “Sing the song if you own the product” games that feature trending items and ASMR skin care routines.

“Kids put this pressure on themselves to be polished like the older girls they look up to,” Zhao said. “It’s not realistic. It’s not attainable. It doesn’t align with the development of preteens.”

Eighth-graders Marley Heller and Sophia Espinoza both indulge in purchasing beauty products from stores such as Sephora and Ulta.

Some of the popular items they have purchased include Drunk Elephant skincare products, Maybelline Sky High mascara and Sol de Janeiro perfume.

However, they do not view themselves as “Sephora kids.”

Heller believes that it is acceptable for seventh-graders and above to use makeup and shop at specialty cosmetic stores like Sephora. Yet, she finds it troubling when children even younger are in those stores acting like sophisticated beauty gurus.

“It’s really weird because they don’t even know what they’re doing when they apply it to their face,” Heller said.

Espinoza echoed Heller’s sentiments, saying that young children should avoid using beauty products.

“They’re very materialistic. They want all the products to make themselves look younger even though they are young,” Espinoza said.

This materialism extends further than ordinary makeup — certain items are idolized, and according to Zhao, those whose personal style adheres to an “aesthetic” are encouraged to consume more in order to conform.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean you follow trends tightly, but they do have a big impact on what I view as fashionable at the moment,” Zhao said. “Of course everybody wants to be fashionable.”

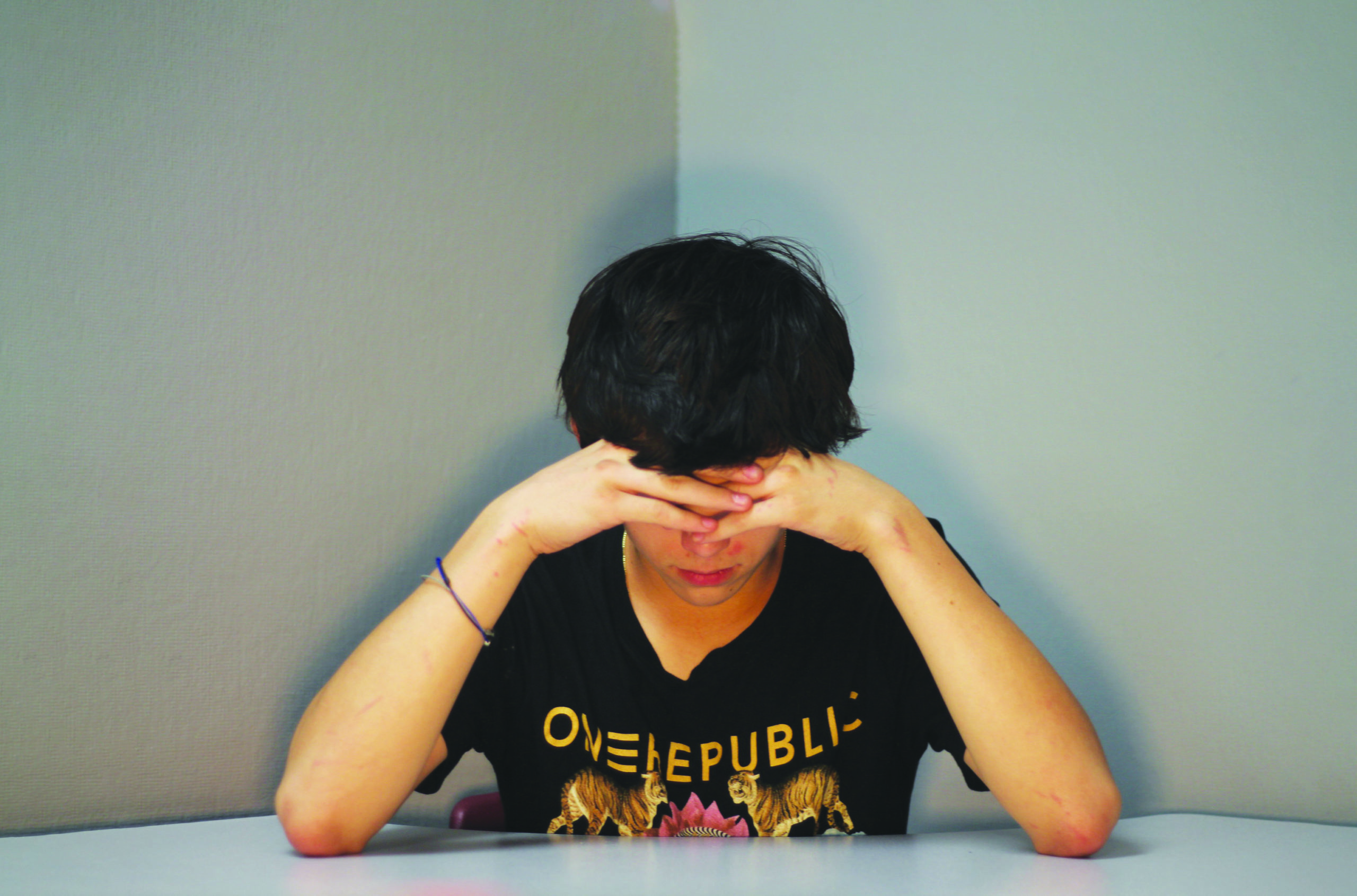

Patricia Jacobsen, dean of student life and math department head, feels disturbed by the young ages of girls using intense anti-aging, skin care and makeup products.

“It’s more indoctrination, or more of society telling girls they need to be beautiful,” Jacobsen said. “Not too many ‘Sephora boys,’ right?”

She holds concerns that female students may feel pressured to conform to these societal beauty standards, sacrificing the time required to excel in other areas.

“This bothers me because if you have a test at 8:20 a.m., and your main focus as a young woman is to make sure your hair is straightened because that’s what society has told you to do, maybe the boys are sleeping for an extra half hour or reviewing for the test,” Jacobsen said.

According to Heller and Espinoza, the constant exposure to idealized images of beauty on social media leads young girls to internalize these unrealistic standards. In addition, it fuels demand in young women for high-end beauty products and spending.

Seeing perfectly styled influencers and models continually online causes impressionable teens to desire to emulate these flawless looks themselves, Heller and Espinoza said.

“Sometimes it sets high beauty standards for people our age,” Heller said. “Seeing really pretty girls and trying to compare yourself to them can be really hard to deal with.”

Zhao attributes this to the decline of online content and stores like Claire’s and Justice, aimed specifically at a preteen audience.

“The blurring of content between age demographics definitely has allowed younger kids to become exposed to more adult content,” Zhao said. “I think companies are well aware of that and I think they’re taking advantage of that.”

According to Zhao, marketing companies intentionally seek out the most attractive influencers and models in the target age demographic to sell their products. Companies may even go beyond the age demographic because younger people admire and aspire to be like older people, especially within the narrow range of high school.

“A 14-year-old admires an 18-year old, but an 18-year-old doesn’t necessarily admire a 60-year-old,” Zhao said.

That, combined with a lack of representation for preteens, has caused them to turn to other role models, Zhao said.

For example, when Zhao was in fifth grade, she stumbled upon a prom dress website. Despite her senior prom being almost a decade away, she ogled at the gorgeous models and intricate dresses, becoming aware of her deficiencies and flaws for the first time.

“I was comparing my prepubescent body to the body of 20 to 23-year-old models, who were then marketing towards high school girls,” Zhao said. “None of the ages in that system matched up, and I think it’s designed that way.”

In addition, from what Zhao has seen online, she believes that there appears to be disproportionately more female beauty influencers than male influencers.

As a result, girls in general are making more decisions about their appearance and their consumption than boys are at a younger age, Zhao said.

To avoid this, Zhao would like to see more stores and online content directed for that in-between age demographic.

“I grew up in the age demographic where Claire’s as a middle schooler was still very much a cool place to go,” Zhao said. “I would like to see more stores like that today.”

Students also identified family influence as a reason why many preteens and teenagers started focusing on makeup and enhancing their appearances.

For example, Heller started wearing mascara in middle school, after her mother told her she should start wearing it to make her eyelashes look longer.

Sophomore Grace Mahan was also introduced to anti-aging practices at a young age from being surrounded by family members who wear makeup.

“My mom, dad and grandma got Botox, so I feel like being around that and social media can give kids the signal that they need to change how they look,” Mahan said.

As a parent, Jacobsen is frequently surprised by the number of products in her daughter’s bathroom. Although she supported her daughter using simple, natural-looking makeup to enhance her features beginning in late middle school, she emphasizes that makeup is not necessary.

“The few times that I have kind of rolled my eyes is if it’s 9 a.m. on a Saturday and when I want to walk the dog, and she has to put mascara on before we go,” Jacobsen said.

For Jacobsen, it is important to strike a healthy balance and foster a strong understanding of what is reasonable for the child’s age.

“I try not to be judgmental about what other parents let their kids do,” Jacobsen said. “But for me, that would not be a choice I would make if I had a 10-year-old again. I hope that my grandkids wouldn’t be encouraged to do that either.”

However, Jacobsen also believes that using skin care and makeup can be enjoyable, not only constricting. She acknowledges the satisfaction derived from the intimate process of getting ready.

Indulging in activities intended to enhance beauty can also be a bonding experience when they are age-appropriate for the child, Jacobsen said.

“I remember when Kaitlyn was two or three, we would paint each other’s nails,” Jacobsen said. “But, I’m not putting anti-aging stuff on her cuticles.”

While Jacobsen uses several products to protect her skin, she fears how preteens are being regularly exposed to the beauty industry and societal standards.

“At 10, you don’t know that you’re not pretty enough until and unless someone tells you that there’s something wrong with you,” Jacobsen said. “I don’t think we’re naturally designed to find all of our flaws and to be so negative with ourselves.”

For Zhao, the outside influence that accomplished this was the Internet. She said that she was being exposed to content that gradually reprogrammed her brain, convincing her that she was lacking and that she required certain products, routines or behaviors to compensate for it.

However, Zhao believes it is an absurd expectation.

“How much anti-aging can you even do as a 13-year-old when you haven’t aged in the first place?” Zhao said.

Today, Zhao considers herself a “skin care minimalist,” sticking to a handful of reliable staples. While she admits that several of her purchases were influenced by current trends, Zhao urges preteens to become cognizant of the reason why they feel that they need certain products.

“I’m not going to lie, it’s fun. But we need to wake up to how much we’re being exploited,” Zhao said.

Retinol

In addition to over-the-counter skin care products, retinol has become a common item falling into the baskets of children.

Retinol is a form of vitamin A, which is used in skin care to treat acne and has anti-aging effects. The use of retinol creams prompts skin cell proliferation as well as collagen production, which in turn can reduce the appearance of wrinkles.

“I think one of the things that isn’t talked about enough is that many girls’ parents use retinol or other anti-aging treatments,” Mahan said. “As a kid, I always wanted to wear makeup and dress like my mom. I wanted to be just like her.”

Retinol is typically recommended for adults starting in their mid-20s. This is around the time collagen production begins to naturally break down with age.

Jacobsen views and treats aging as a gift that grows as she progresses through the stages of her life.

“Yeah, maybe I have wrinkles or sunspots, but I don’t need retinol,” Jacobsen said. “I earned all of those running. I’ve traveled a lot, and every scar that I have is from living life. I don’t like the idea that you have to look airbrushed.”

While retinoid use can cause temporary side effects like dryness and irritation even in adults, these effects tend to be more common and severe in children because children’s skin is still developing and more sensitive.

While over-the-counter retinol products do not pose a significant concern in side effects and symptoms in children, stronger prescription retinoids such as isotretinoin (a prescription oral retinoid medication to treat severe or cystic acne) and tretinoin (a topical retinoid) have been associated with bone abnormalities when used by children.

Because children’s bones are still actively growing, retinoids pose the risk of prematurely halting growth plate development, leading to altered bone structure.

Skeletal abnormalities are relatively common side effects, occurring in 25-90% of pediatric cases depending on the retinoid and dose.

— By Lauren Lu & Zema Nasirov